By: Phoebe Ingraham Renda

From Oculus gaming systems to Apple’s Vision Pro, Pitt students are no strangers to virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies. However, for the first time in fall 2023, 115 School of Pharmacy students used this technology to step into their studies during their Pharmacotherapy of Cardiovascular Disease course.

“We’re teaching students how to use medications to treat different types of heart disease—but before they can do that effectively, they need a good foundational review of heart anatomy,” says James “Jim” Coons, course instructor and professor in the Department of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, School of Pharmacy. The course is part of the Doctor of Pharmacy program, a six-year entry-level professional program.

While the course has used Pitt’s Peter M. Winter Institute for Simulation Education and Research human patient simulators since the mid-2000s to offer students an interactive learning experience, anatomy lessons remained primarily lecture based.

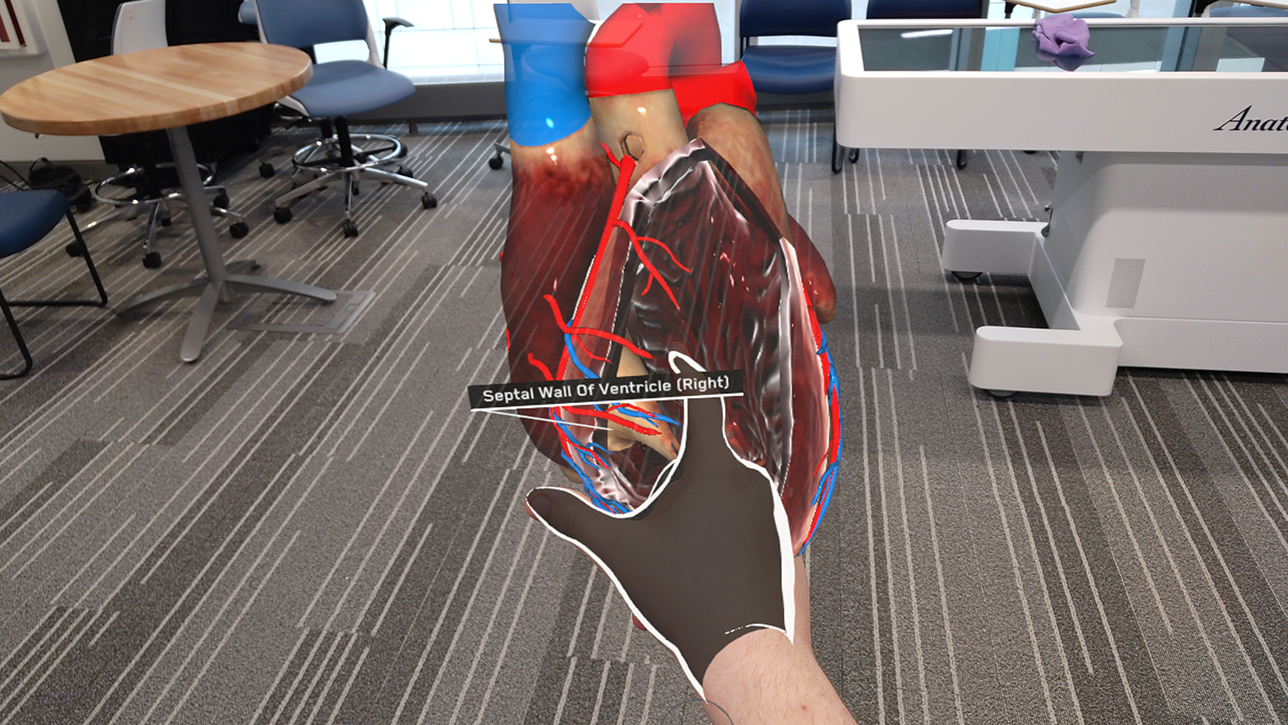

Pharmacy students explore their cardiac anatomy lessons in 3D using HoloLens 2 AR headsets in Alan Magee Scaife Hall. Photo credit: Lawrence Kobulinsky.

With a little help from Pitt Health Sciences Information Technology (HSIT), last year’s students turned away from PowerPoint slides and immersed themselves in anatomy lessons using an Anatomage Table, akin to a dining table-sized iPad, and HoloLens 2 AR headsets.

“It’s a million miles away from what Jim used to do,” says Lawrence “Larry” Kobulinsky, an instructional designer who has helped support the course since 2013. “You can show something three-dimensionally and manipulate it by turning it or removing sections, which is something you could never have imagined just a few years ago.”

The combination of Anatomage modules and AR technologies for various disease states and diagnostics dramatically enriched student learning. Standing in front of a 3D heart, they can now explore beyond the heart’s chambers. Students can interact with the heart’s arteries and conduction system, examine healthy and unhealthy cardiac anatomy, and monitor medications and see where they work in the heart.

Using HoloLens technology, Pitt School of Pharmacy students interact hands-on (virtually) with 3D heart anatomy. Photo credit: Alexi Zukas

Coons and Kobulinsky are extending their work with AR and patient simulator training into the virtual world. They are actively creating a realistic VR clinical case with help from SimX—a leading VR simulation training platform for physicians, military and emergency medical responders.

“Once you’re in the virtual environment, you can pick up an electronic medical record (EMR) tablet and scroll through pages, talk on the phone, view patient information, insert IVs and make order entries off the EMR tablet,” Kobulinsky says.

In the VR case, students will interact with a critically ill patient, nurses and physicians within an infectious disease setting. As students interact with their virtual patient, they may see changes in labs within the EMR as well as real-time changes, like a drop in blood pressure or other signs that the patient has become unstable. Their patient may even develop new complaints to consider.

“This technology transforms the way our students learn and transforms the interprofessional learning environment so that students can practice in an interprofessional manner,” says School of Pharmacy Dean Amy Seybert. “It adds a realism to their learning—they have to react to how the patient responds in real time so they can adjust medication therapy or talk to the interprofessional team about a new approach.”

Patient detail even reaches down to genetics to incorporate pharmacogenomics training, in which students look for certain genes that can predict response to medications and affect treatment recommendations.

“Pharmacogenomics comes up a lot in the world of cardiology,” says Coons. He explains that sensitivity to anticoagulants, like warfarin, and other medications that patients take after receiving a stent (a mesh coil that helps keep an artery open) can differ based on genetics.

Coons and Kobulinsky hope to receive a beta testing copy of their VR case this spring to perfect it for use in the fall. In the fall class, Coons and Kobulinsky will also incorporate assessments to show that teaching with these technologies enhances student learning and retention. “It will definitely be a part of the future of pharmacy education,” says Seybert.

Growing up with iPads and novel technologies, Kobulinsky notes, today’s student expectations for learning are different than those of students who came here 15-20 years ago. As digital natives, students easily become immersed and engaged in trying to help their simulated patient and, in turn, recall information they have read, heard or seen in other courses. “This allows them to bring it all together in this digitally connected world that they’re used to,” says Seybert.

This fall, the class will take place in a brand-new AR/VR lab, located on the mezzanine floor of Alan Magee Scaife Hall, that will be available to all health sciences schools. The new space will feature an assortment of AR/VR headsets (including HoloLens 2, Meta Quest 3 and Vive Pro 2), an Anatomage Table and a large-scale video recording studio for live streaming and recording lectures.

“We are looking at how Pharmacy used the technology last year in planning for the new space,” says Jane Alexander, assistant director of education technology for HSIT. “We hope to gain interest from other groups in the health sciences and showcase what the technology can do and how it can benefit learning.”

Seybert, Coons and Kobulinsky look forward to seeing the technology work its way into other School of Pharmacy courses and inspire other courses within the health sciences schools to transform historically didactic lectures into interactive and 3D learning experiences.

“This is Dr. Shekhar’s vision for the health sciences—we’re thrilled to be a part of it and align it with each of the health sciences schools,” says Seybert.

Coons watches his student explore life-sized cardiac and circulatory anatomy on an Anatomage Table. Photo credit: Lawrence Kobulinsky.